| Home | Log In | Register | Our Services | My Account | Contact | Help |

You are NOT currently logged in

Register now or login to post to this thread.

BLINX and you've missed it, the next google multi bagger!!! (BLNX)

Still Waiting - 25 Jul 2008 23:22

With video search set to be the next big growth area BLNX have the software the likes of Microsoft, Google and NewsCorp would love to have.

In fact BLNX have done deals with most of these, the most recent being the UtargetFox deal which has been reported in the USA but not RNS'd in the UK.

Alexa rankings confirm the continued growth in usage as its viral effect spreads:-

http://www.alexa.com/data/details/traffic_details/blinkx.com

The ITN RNS confirms blnx is the best in the market and is growing fast:-

Leading News Organization ITN Extends Advertising Deal with blinkx Based on Proven Campaign Success

blinkx Selected to Power Advertising across ITN Website and Syndication Partner Sites

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIF. - July 2, 2008 - blinkx, the world's largest and most advanced video search engine, today announced that it has won an extension contract that will augment the scope of its advertising partnership with ITN, one of the world's leading news and multimedia content companies. Under the terms of the new agreement, ITN will use AdHoc, blinkx's patented contextual advertising platform for online TV and video, to serve advertisements on the ITN website and its syndication partner sites, including Bebo.

Through AdHoc, ITN has already been effectively monetizing its premium news content on the blinkx.com network for over six months. During this time, ITN achieved a significantly better return, greater search volume, and higher monetization through blinkx than through other syndication partners.

AdHoc uses blinkx's patented speech-to-text transcription and visual analysis technology to understand video content more thoroughly and effectively than any other service today, and can therefore dynamically place the most pertinent advertising against it. The AdHoc platform offers media companies and advertisers a unique value proposition -- video advertising which combines the emotive power of TV promotion, with the relevance and utility of contextual search advertising.

The confluence of ITN's premium TV content, blinkx's extensive syndication network, and AdHoc's uniquely powerful targeting capabilities was a formula for success. By extending its partnership with blinkx, ITN aims to achieve similar returns by leveraging the AdHoc platform to deliver contextually relevant video advertising on its own website and across its distribution partner sites.

'We're thrilled to be broadening our relationship with ITN,' said Suranga Chandratillake, founder and CEO of blinkx. 'News content is one of the most popular categories of online video and there's clearly a tremendous opportunity for monetization. The success of our partnership with ITN is evidence that the blinkx AdHoc platform is a uniquely powerful solution for online video advertising today.'

'We've been delighted with the results of our partnership with blinkx and are looking forward to implementing the AdHoc technology on our site,' said Nicholas Wheeler, managing director, ITN On. 'blinkx AdHoc has proven that it can achieve significant monetization of our content, effective marketing for advertisers and, most importantly, a useful, non-disruptive experience for our audience.'

As a pioneer in video search technology, blinkx has built a reputation as the most effective way to search new forms of online content such as video. With more than 350 partners and 26 million hours of indexed video and audio content, including favorite TV moments, news clips, short documentaries, music videos, video blogs and more, blinkx uses advanced speech recognition technology to deliver results that are more accurate and reliable than standard metadata-based keyword searches.

IanT(MoneyAM)

- 23 Sep 2010 12:58

- 2950 of 6187

- 23 Sep 2010 12:58

- 2950 of 6187

nope it was a change at this end, but the F5 cleared the cache at your end,

Ian

Ian

Haystack

- 23 Sep 2010 13:05

- 2951 of 6187

- 23 Sep 2010 13:05

- 2951 of 6187

Shouldn't it be CTRL-F5 to clear the cache. F5 just refreshes the page.

IanT(MoneyAM)

- 23 Sep 2010 13:06

- 2952 of 6187

- 23 Sep 2010 13:06

- 2952 of 6187

Haystack,

makes no difference to clear this problem, either or will suffice in this situation

Ian

makes no difference to clear this problem, either or will suffice in this situation

Ian

tabasco - 23 Sep 2010 13:12 - 2953 of 6187

Haystackffs Ian has rectified the problemIan.what button do I press to get shot of Haystack?

ptholden

- 23 Sep 2010 19:57

- 2954 of 6187

- 23 Sep 2010 19:57

- 2954 of 6187

Mp. There was and is no bear attack on Blnx, nor Market manipulation. Whlist I do not deny MMs can move a SEAQ stock if they so choose, Blnx is a SetsMM stock and not so prone to MM control. I believe this stock is overbought and both shorters and profit takers have moved in, simple Market forces. Oh, and please do not quote buy/sell ratios , anyone with a DMA account can sell at the offer and buy at the bid through the book, a simple fact which seems to escape the average investor with little knowledge of the markets.

moneyplus

- 23 Sep 2010 23:56

- 2955 of 6187

- 23 Sep 2010 23:56

- 2955 of 6187

pth--thanks for your reply. Not many small investors have a DMA account and I merely think that with a bit of bot selling an avalanche of sells can build up as shorters/profit takers jump on board. so we basically agree and chartists would also agree. It's the sharp falls which reverse often in under an hour which I find suspicious. I bow to your greater knowledge and accept I'm wrong. I feel buy and hold suits me best, I'd need a training course to take on short term trading.

ptholden

- 24 Sep 2010 06:46

- 2956 of 6187

- 24 Sep 2010 06:46

- 2956 of 6187

Mp, no greater knowledge at this end of the keyboard, nor are you necessarily wrong! But you always find posters moaning about treeshakes and such like when stocks reverse when generally it's simple Market dynamics.

hilary

- 24 Sep 2010 07:47

- 2957 of 6187

- 24 Sep 2010 07:47

- 2957 of 6187

PTH,

With setsMM you've generally got no idea who's REALLY on the bid and offer. A market maker can both advertise his price and at the same time be working an order and controlling the price under a veil of secrecy.

One of the concepts of setsMM was that it gave greater market transparency to retail punters. In reality, it simply enables the market makers to conceal their true mission. Under SEAQ it's quite easy to identify who's controlling the price, and that's not so under setsMM.

With setsMM you've generally got no idea who's REALLY on the bid and offer. A market maker can both advertise his price and at the same time be working an order and controlling the price under a veil of secrecy.

One of the concepts of setsMM was that it gave greater market transparency to retail punters. In reality, it simply enables the market makers to conceal their true mission. Under SEAQ it's quite easy to identify who's controlling the price, and that's not so under setsMM.

ptholden

- 24 Sep 2010 08:22

- 2958 of 6187

- 24 Sep 2010 08:22

- 2958 of 6187

Hils, I'm aware MMs can also trade as you succinctly explain, but that isn't to say that they do so all the time. My point is punters always find it easy to blame the MMs when a stock tumbles, whch clearly is not always the case.

tabasco - 24 Sep 2010 08:25 - 2959 of 6187

Hilary.perhaps Peter is a gynaecologist in his spare time?he seems to enjoy rubbing people up the wrong way?

tabasco - 24 Sep 2010 08:33 - 2960 of 6187

Peter.your spin is in line with your trade

hilary

- 24 Sep 2010 08:38

- 2961 of 6187

- 24 Sep 2010 08:38

- 2961 of 6187

Very sharp, Tabster.

:o)

:o)

tabasco - 24 Sep 2010 09:53 - 2962 of 6187

Try this

http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/console/b00tt6kj/The_Bottom_Line_23_09_2010

Click to 24 minutes The Doctor talking of Autonomy directionvery interestingAutonomy getting into the consumer spacecould that be a link with BLNX."Cheap" is going live anytimeI dont believe in coincidences?.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/console/b00tt6kj/The_Bottom_Line_23_09_2010

Click to 24 minutes The Doctor talking of Autonomy directionvery interestingAutonomy getting into the consumer spacecould that be a link with BLNX."Cheap" is going live anytimeI dont believe in coincidences?.

tabasco - 24 Sep 2010 12:56 - 2963 of 6187

The Doctor is famous for keeping secrets and fcuking traders uplol...lol...lol... it looks like his adopted son is from the same ilkso when The Doctor says he is about to launch a consumer productand starts with very favourable sponsorship deals with Spurs and Formula 1 team Mercedes I find it hard to believe even he could keep this venture so quite unless it was achieved by another company he was close toknow any companies that are about to launch a consumer product?. any guesses?

tabasco - 24 Sep 2010 13:56 - 2964 of 6187

Check the buy trades every 15 minutes and always in the 200s226...237...240...etc....amazingnext one is due at 2-00...my guess is for 243...any other guesses?

Haystack

- 24 Sep 2010 14:36

- 2965 of 6187

- 24 Sep 2010 14:36

- 2965 of 6187

tabasco

Have you read this

http://www.moneyam.com/TradersRoom/posts.php?tid=1913

15 Jan 2004

Crocodile takes on the robots - Shares Magazine article

David Croc Anderson used to sell computers, but he really began making money out of them when he spotted computerised trades on the stock market. By Jeremy Lacey

For David Anderson, aka Croc, it was a Matrix kind of experience the moment he suddenly realised that what he was seeing out there was being run by machines, not people.

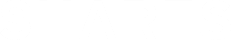

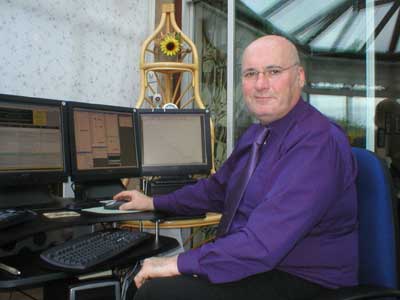

Anderson is a doyen among day traders and a stalwart of the MoneyAM bulletin boards, where he appears under the user name Crocodile. The crocodile in question is a now rather battered looking cuddly toy which sits on a sofa in the Anderson conservatory, and the two of them go way back.

My background is in computers, he explains. I had my own business from when I was 20-odd years of age until I was in my mid-forties. My company was originally called Anderson Computer Systems. It was doing OK, but after I changed the name to Crocodile Computers suddenly we tripled our turnover in one year.

So what took him from selling computers to sitting in front of them trading shares?

I saw the writing on the wall when Tescos started selling computers they were open 24 hours a day and I thought, this is going to get worse and worse and worse. Six or seven years ago, I decided it was time to get out.

Anderson had become interested in trading and was active on the bulletin boards. I got to the stage when I thought, OK, I can do this for a living. I had an offer for the business, so I thought I would sell it and see if I could survive the year share trading. Much to my amazement, I managed to bring in somewhere between 5% and 10% a month on my capital.

He was trading away happily, making a steady if unspectacular profit, when something odd struck him about the figures flickering across his screens. I noticed there were trades going through that were not being put in by humans and Im not talking about aliens here, either, Im talking about computers.

Like Neo, the brooding hero of the Matrix movies whose world is exposed as a stream of binary code, Anderson realised it was the machines that were pulling the strings. The first one I noticed was on ICI, a 50,000 buy at the top of the order book. I was short on it selling and hoping to buy back at a lower price. There was only one order left so I thought when that goes then Im going to be in the money.

Anyway, the 50,000 disappeared and instantly turned up with another 50,000. I thought that blokes got fast fingers! I waited another minute and 50,000 got taken out and instantly came back. I wasnt too suspicious at this point, but then it got taken out 10 times in one session.

I opened up a thread on one of the bulletin boards saying Robot traders could be damaging your wealth. Much to my surprise, that night I had a phone call from Merrill Lynch to ask me where Id got that information from. I thought thats it, thank you very much indeed!

From there, I started noticing other computerised trades and eventually realised that nearly every share on the stock market is traded by computers constantly, and that there are different types of computer trade. Anderson takes credit for coining the term robot trade, which became shortened to bot and is now part of the common parlance of traders when they talk about automated computerised trading systems.

A solid Brummie, Anderson is an unlikely Neo. He works from home in the West Midlands town of Sedgley, perched on a hilltop with an uninterrupted view across miles of rural tranquillity towards the Welsh mountains.

He has done well as a professional trader: evidence his second home in Le Touquet. These days he makes a few bob by letting others in on his secrets and would-be traders regularly pack into the Sedgley conservatory for training sessions. He cautions novices against unrealistic expectations, though.

If you can make somewhere between 20% and 100% a year on your capital through share trading, then youre a very good trader and beating most people in the City. Anyone planning to make a living out of trading needs to start by working out exactly how much money he or she needs to live on, he says, and then be very realistic about the potential returns.

Ive had some young traders in here who want to be professional. I ask them how much money they have to invest and they say 10,000, so I ask how much they need to live on and they say a minimum of 3000 a month. Which means they have to make 30% every single month, and thats without any growth in actual capital. Theres no realism in there whatsoever. If you could pick a share that would give you a 30% rise each month, youd have the best share tip ever. But back to the bots: what were Merrill Lynch and the rest of the big investment houses up to, and how many other people knew what was going on?

Apparently within the industry, they knew roughly how it was done. If an institution wants to buy, say, three million shares it cant just go to the order book with that because all the sellers would instantly disappear, so they have to split them into smaller amounts. In the industry they used to call these small amounts tranches and most people thought these tranches were put in by traders but its far more efficient to let the computer do this for you.

The good thing for the trader is it shows you where there are big orders its a giveaway. It tells you the shares you ought to be considering buying or selling and also not to go against them.

After I started to notice this it doubled my profitability from 5% to 10% a month within a year. And its not difficult to spot. Anderson showed me one sure sign to watch for on his Level 2 screens: small random numbers of shares, say 545 or 675, where it would appear difficult to cover the trading costs but which nevertheless were constantly going through. By drip-feeding their buys and sells every hour, every day, the institutions can move huge numbers of shares without alerting the market, and thats where the computers come in. If youre a very large broker like Merrill Lynch or whatever, you cant have 300 traders sitting in front of a screen dealing all day. They would have to have a huge, expensive trading room, so its traded on a computer.

Different types of robot have been identified, like the piranha bot, which takes tiny small bites and keeps nibbling away. Or the sheep bot, which always follows wherever you lead it. I watched while Anderson found a sheep bot and steadily upped the price. Its programmed so that it always has to be at the top, so if you go in front of it, it joins you even if you only put in 10 shares at a halfpenny above it. If you have a position on a share, you can force the price up and take control of the stock.

You could move the share price up 10p to 15p with one order and because you know this sheep bot is about to move up, you can be ready to sell as soon as it gets there, so short it.

If you catch the right one on the right day you can make enormous amounts of money on it. He recalls one rewarding spell of trading in France last summer when he made a 2500 profit in 15 minutes. Once you know how these computer systems work, you can take advantage of them. Its like having a repeat jackpot on a fruit machine, until someone spots what youre doing and stops it.

Knowing how the computers work and learning to spot the bots is perhaps easier than it sounds. When Anderson points out what is happening on the charts, it all looks blindingly obvious but some of us might need a bit of practice before we can do it for ourselves. For readers who want to find out more, a good starting point is Andersons website, www.snappytrader.com.

While recognising bots gives traders a chance to make quick profits on one stock in a single trading session, there is also money to be made by grasping the bigger picture of how computers play the market and spotting the support and resistance levels that decide the ranges they trade in.

The large institutions and hedge funds put the money in the top and just let the computer trade the market, says Anderson. Once you can spot the line, you can see where the computer is currently trading the market. Theres no point trying to stand up to the computer, because eventually it always wins.

Analysis of the charts gives Anderson a pretty good idea of where he thinks the computers are going to start buying and selling the market. At the same time, he says, the largest stocks are virtual trackers, moving in line with the index. If you take a one-year chart of Barclays, say, and overlay the FTSE, you can see the correlation. If youre doing technical analysis on Barclays are you actually doing technical analysis on it or on the market itself? Because theres such a strong correlation.

Which means that if, for example, you can predict the market is going to run out of steam today and the computers are going to start selling, you can assume the same will apply to Barclays and any other quasi-trackers.

The canny trader has an additional opportunity here, because there is a slight delay between the movement in the index and that of the individual stock. A lot of traders get slightly paranoid because Barclays is going up and the instant they buy it it starts falling, while the second they get out it starts going up again. If theres a big move on the market you can often get a bargain because some of the traffic hasnt yet moved.

His conviction that the big institutions computers trade the top stocks as index trackers led Anderson to the idea that dividends create opportunities.

Logically, the price of a share going ex-dividend should fall by the amount of that dividend: eg if a stock closes at 120p on a Tuesday and goes ex-dividend on Wednesday with a 7p payout, it should open at 113p. But it doesnt always work out like that, and according to Anderson one reason is that computers are dumb.

The computers have no idea that a companys paid a dividend all theyll see is the fact that its price has dropped below the percentage for the FTSE. The nice thing is if for example you have a company paying out a 6% or 7% dividend, youll know darn well that as a tracker its going to be brought back into line with the index.

David Andersons world is a fascinating one in which a lone trader patiently researching the charts is able to milk opportunities created by some of the worlds biggest investment houses. Machines rule but man makes a nice little earner.

Have you read this

http://www.moneyam.com/TradersRoom/posts.php?tid=1913

15 Jan 2004

Crocodile takes on the robots - Shares Magazine article

David Croc Anderson used to sell computers, but he really began making money out of them when he spotted computerised trades on the stock market. By Jeremy Lacey

For David Anderson, aka Croc, it was a Matrix kind of experience the moment he suddenly realised that what he was seeing out there was being run by machines, not people.

Anderson is a doyen among day traders and a stalwart of the MoneyAM bulletin boards, where he appears under the user name Crocodile. The crocodile in question is a now rather battered looking cuddly toy which sits on a sofa in the Anderson conservatory, and the two of them go way back.

My background is in computers, he explains. I had my own business from when I was 20-odd years of age until I was in my mid-forties. My company was originally called Anderson Computer Systems. It was doing OK, but after I changed the name to Crocodile Computers suddenly we tripled our turnover in one year.

So what took him from selling computers to sitting in front of them trading shares?

I saw the writing on the wall when Tescos started selling computers they were open 24 hours a day and I thought, this is going to get worse and worse and worse. Six or seven years ago, I decided it was time to get out.

Anderson had become interested in trading and was active on the bulletin boards. I got to the stage when I thought, OK, I can do this for a living. I had an offer for the business, so I thought I would sell it and see if I could survive the year share trading. Much to my amazement, I managed to bring in somewhere between 5% and 10% a month on my capital.

He was trading away happily, making a steady if unspectacular profit, when something odd struck him about the figures flickering across his screens. I noticed there were trades going through that were not being put in by humans and Im not talking about aliens here, either, Im talking about computers.

Like Neo, the brooding hero of the Matrix movies whose world is exposed as a stream of binary code, Anderson realised it was the machines that were pulling the strings. The first one I noticed was on ICI, a 50,000 buy at the top of the order book. I was short on it selling and hoping to buy back at a lower price. There was only one order left so I thought when that goes then Im going to be in the money.

Anyway, the 50,000 disappeared and instantly turned up with another 50,000. I thought that blokes got fast fingers! I waited another minute and 50,000 got taken out and instantly came back. I wasnt too suspicious at this point, but then it got taken out 10 times in one session.

I opened up a thread on one of the bulletin boards saying Robot traders could be damaging your wealth. Much to my surprise, that night I had a phone call from Merrill Lynch to ask me where Id got that information from. I thought thats it, thank you very much indeed!

From there, I started noticing other computerised trades and eventually realised that nearly every share on the stock market is traded by computers constantly, and that there are different types of computer trade. Anderson takes credit for coining the term robot trade, which became shortened to bot and is now part of the common parlance of traders when they talk about automated computerised trading systems.

A solid Brummie, Anderson is an unlikely Neo. He works from home in the West Midlands town of Sedgley, perched on a hilltop with an uninterrupted view across miles of rural tranquillity towards the Welsh mountains.

He has done well as a professional trader: evidence his second home in Le Touquet. These days he makes a few bob by letting others in on his secrets and would-be traders regularly pack into the Sedgley conservatory for training sessions. He cautions novices against unrealistic expectations, though.

If you can make somewhere between 20% and 100% a year on your capital through share trading, then youre a very good trader and beating most people in the City. Anyone planning to make a living out of trading needs to start by working out exactly how much money he or she needs to live on, he says, and then be very realistic about the potential returns.

Ive had some young traders in here who want to be professional. I ask them how much money they have to invest and they say 10,000, so I ask how much they need to live on and they say a minimum of 3000 a month. Which means they have to make 30% every single month, and thats without any growth in actual capital. Theres no realism in there whatsoever. If you could pick a share that would give you a 30% rise each month, youd have the best share tip ever. But back to the bots: what were Merrill Lynch and the rest of the big investment houses up to, and how many other people knew what was going on?

Apparently within the industry, they knew roughly how it was done. If an institution wants to buy, say, three million shares it cant just go to the order book with that because all the sellers would instantly disappear, so they have to split them into smaller amounts. In the industry they used to call these small amounts tranches and most people thought these tranches were put in by traders but its far more efficient to let the computer do this for you.

The good thing for the trader is it shows you where there are big orders its a giveaway. It tells you the shares you ought to be considering buying or selling and also not to go against them.

After I started to notice this it doubled my profitability from 5% to 10% a month within a year. And its not difficult to spot. Anderson showed me one sure sign to watch for on his Level 2 screens: small random numbers of shares, say 545 or 675, where it would appear difficult to cover the trading costs but which nevertheless were constantly going through. By drip-feeding their buys and sells every hour, every day, the institutions can move huge numbers of shares without alerting the market, and thats where the computers come in. If youre a very large broker like Merrill Lynch or whatever, you cant have 300 traders sitting in front of a screen dealing all day. They would have to have a huge, expensive trading room, so its traded on a computer.

Different types of robot have been identified, like the piranha bot, which takes tiny small bites and keeps nibbling away. Or the sheep bot, which always follows wherever you lead it. I watched while Anderson found a sheep bot and steadily upped the price. Its programmed so that it always has to be at the top, so if you go in front of it, it joins you even if you only put in 10 shares at a halfpenny above it. If you have a position on a share, you can force the price up and take control of the stock.

You could move the share price up 10p to 15p with one order and because you know this sheep bot is about to move up, you can be ready to sell as soon as it gets there, so short it.

If you catch the right one on the right day you can make enormous amounts of money on it. He recalls one rewarding spell of trading in France last summer when he made a 2500 profit in 15 minutes. Once you know how these computer systems work, you can take advantage of them. Its like having a repeat jackpot on a fruit machine, until someone spots what youre doing and stops it.

Knowing how the computers work and learning to spot the bots is perhaps easier than it sounds. When Anderson points out what is happening on the charts, it all looks blindingly obvious but some of us might need a bit of practice before we can do it for ourselves. For readers who want to find out more, a good starting point is Andersons website, www.snappytrader.com.

While recognising bots gives traders a chance to make quick profits on one stock in a single trading session, there is also money to be made by grasping the bigger picture of how computers play the market and spotting the support and resistance levels that decide the ranges they trade in.

The large institutions and hedge funds put the money in the top and just let the computer trade the market, says Anderson. Once you can spot the line, you can see where the computer is currently trading the market. Theres no point trying to stand up to the computer, because eventually it always wins.

Analysis of the charts gives Anderson a pretty good idea of where he thinks the computers are going to start buying and selling the market. At the same time, he says, the largest stocks are virtual trackers, moving in line with the index. If you take a one-year chart of Barclays, say, and overlay the FTSE, you can see the correlation. If youre doing technical analysis on Barclays are you actually doing technical analysis on it or on the market itself? Because theres such a strong correlation.

Which means that if, for example, you can predict the market is going to run out of steam today and the computers are going to start selling, you can assume the same will apply to Barclays and any other quasi-trackers.

The canny trader has an additional opportunity here, because there is a slight delay between the movement in the index and that of the individual stock. A lot of traders get slightly paranoid because Barclays is going up and the instant they buy it it starts falling, while the second they get out it starts going up again. If theres a big move on the market you can often get a bargain because some of the traffic hasnt yet moved.

His conviction that the big institutions computers trade the top stocks as index trackers led Anderson to the idea that dividends create opportunities.

Logically, the price of a share going ex-dividend should fall by the amount of that dividend: eg if a stock closes at 120p on a Tuesday and goes ex-dividend on Wednesday with a 7p payout, it should open at 113p. But it doesnt always work out like that, and according to Anderson one reason is that computers are dumb.

The computers have no idea that a companys paid a dividend all theyll see is the fact that its price has dropped below the percentage for the FTSE. The nice thing is if for example you have a company paying out a 6% or 7% dividend, youll know darn well that as a tracker its going to be brought back into line with the index.

David Andersons world is a fascinating one in which a lone trader patiently researching the charts is able to milk opportunities created by some of the worlds biggest investment houses. Machines rule but man makes a nice little earner.

tabasco - 24 Sep 2010 14:54 - 2966 of 6187

Haystackinteresting readthanks!.I particularly like the last sentence.

Haystack

- 24 Sep 2010 14:56

- 2967 of 6187

- 24 Sep 2010 14:56

- 2967 of 6187

It is worth reading the whole thread if you have a traders sub.

moneyplus

- 24 Sep 2010 15:09

- 2968 of 6187

- 24 Sep 2010 15:09

- 2968 of 6187

tabasco have you looked at ATUK? I'm in early days--very like blnx for potential imo--what do you think? oct 7th is the main launch and google have just upped the free advertising to 15 million.

tabasco - 24 Sep 2010 15:42 - 2969 of 6187

Shorters getting turned over again.when are they going to learn this is nailed on!